Greetings fellow Clubbies and welcome to the 12th “As You Were!” post (doesn’t time go by when you’re not watching the clock or having a nap). November is upon us and back in the day we were trying to juggle our Trade Cert and Education exams (in 1964, School Cert started on the 16th) with the increasingly strident demands of the SSM to get out on the parade ground and practise for Grad parade. If we were soldier trainees and not on a course we became his captives. In 1966, November was also the month in which the School and Camp Cross Country races were held, together with the annual 30 mile march. In 1965, my diary tells me November was a month in which I had an outbreak of boils, including one on the back of my head which was wrapped in a large bandage by the folk at MIR. I couldn’t wear my beret and remember getting looked at oddly by officers when I saluted them. Ah, those were the days.

November was also the month in 1918 when the armistice was signed between the World War I allies and Germany. It took effect at 1100 on the 11th of November (the 11th month). National commemorations of Armistice Day this year have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and will take the form of Acts of Remembrance (wreathlaying ceremonies), which will be held at the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior. They will not be public ceremonies but will include veteran and government representatives. Local Armistice Day celebrations will continue to be held. Armistice Day celebrations in NZ commenced in 1919. Over the next two years, they were disrupted by the global influenza epidemic. The image shows an Armistice Day parade in Levin (possibly 1919).

November was also the month in 1918 when the armistice was signed between the World War I allies and Germany. It took effect at 1100 on the 11th of November (the 11th month). National commemorations of Armistice Day this year have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and will take the form of Acts of Remembrance (wreathlaying ceremonies), which will be held at the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior. They will not be public ceremonies but will include veteran and government representatives. Local Armistice Day celebrations will continue to be held. Armistice Day celebrations in NZ commenced in 1919. Over the next two years, they were disrupted by the global influenza epidemic. The image shows an Armistice Day parade in Levin (possibly 1919).

Tribute – One of Our Own

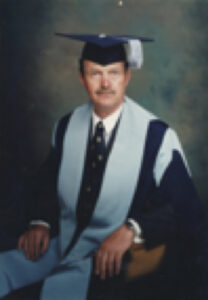

Colonel Brian Robert Hampton Monks, Cross of Gallantry with Silver star (SVN), Greville Class

The Monk’s boys, Brian and Geoff, both ex-cadets and Richard, a direct entry through Portsea, have stamped their mark more than most families on the development of New Zealand’s regular Army. Here they are from the left: Geoff, Brian and Richard – and all Infantry!

The Monk’s boys, Brian and Geoff, both ex-cadets and Richard, a direct entry through Portsea, have stamped their mark more than most families on the development of New Zealand’s regular Army. Here they are from the left: Geoff, Brian and Richard – and all Infantry!

This tribute is in the form of a eulogy delivered by Geoff (Weir Class) at Brian’s funeral. He says it all.

Good morning ladies and gentlemen. I am Geoffrey Monks. I am Brian’s youngest brother and it is my honour to greet you all today. Firstly I greet Brian’s family from far and wide and all of the old soldiers and other friends gathered here today. I extend too a particularly warm welcome to those stalwarts of V6 Rifle Company who have come to honour their old commander and to the personnel fielded by 1 RNZIR.

Nau mai haere mai. Kia ora tatau. Ko au te teina o Brian me te tuawha o to matau whanau. Ko Geoffrey toku ingoa.

E mihi ana ki te whanau o Brian Robert Hampton Monks.

E mihi ana ki nga hoa tawhito i huihui mai ki konei.

E mihi ana ki nga morehu o te whare o Tumatauenga, kua hui mai nei tatou i tenei ra, whakahirahira kia maumahara tonu tatou kia ratou i hingatu i te mura o te ahi.

Ki nga hoia o V6 Rifle Company me 1RNZIR he mihi nui. He nui te honore ki to rangatira o mua.

Brian was born on 1 June 1935 in the small garrison town of Devizes in Wiltshire. He was the first son of a soldier and the fourth generation of soldier sons born into our family. When two years old our father, together with wife and son, returned to his regiment which was then stationed in Butterworth in northern Malaya. This was where Brian began his soldiering…. and Richard was born.

Our father was then seconded to the Malay Regiment as a WO Instructor before being commissioned and transferred to the 1st Battalion of that regiment as a Company 2ic. The household then moved; first to Malacca, where Peter and I were born, and then to Singapore. Brian’s enduring memory of those years was as a member of that privileged band of warriors guarding the gates to the Empire. That perception came crashing down around his ears (literally) when the Japanese bombing and strafing attacks began in late December of 1941. We were forced to flee before the fatally flawed defences of the island fortress failed entirely.

Not yet 7, Brian became the man of the house. We boarded the MV Charon bound for Durban in South Africa on 8 January 1942. My mother carried my twin brother and me, Richard carried his Teddy Bear and Brian carried all of our worldly possessions in two small suitcases. Father stayed behind, still in defence of the Empire. Brian’s first experience of being under direct fire was when Japanese fighters and torpedo bombers destroyed most of our naval escort and several of the passenger ships in the Malacca and Sunda Straits, thereby causing our redirection onto the shorter passage to Freemantle in Western Australia. The International Red Cross discovered kin in Wellington and we were soon relocated by train and troop ship to join a part of my father’s family that had migrated to New Zealand between the wars.

This proved to be a temporary relocation for us. Our relatives’ small Seatoun house could not accommodate five extra folk, and we were soon moved on. We were relocated to a railway goods wagon that was being used as a primitive batch on Otaki Beach. Not having been raised to be a pioneer, Mother did not cope very well. We children were in and out of orphanages until Brian was rescued by a benevolent Christian family and placed as a boarder in Wellesley College in Days Bay. I next saw him in about 1946 after our father had been repatriated to NZ, having miraculously survived the privations of the Burma Railway.

Having tried and failed to be accepted by the Parachute Regiment, (except as a boy drummer) at the age of 15 Brian set sail back to New Zealand alone to join the Regular Force Cadet Unit. The rest of the family straggled back nearly a year later at our mother’s insistence. It was Brian’s plan to complete his education as a cadet and if he had not won a commission by the time he was 19 to return to the UK and enlist as a Para. He had to wait for a few months with the family of a school chum in Trentham, until he turned 16 in June 1951, before joining Williams Class*.

He gained his School Certificate and University Entrance at the Cadet School, was posted as a Private soldier to the School of Infantry, achieving the rank of Cpl in quick order. He attended a very early post- war OCTU in 1955 and was posted back to the School of Infantry as a 2 Lt I/C Tactics Wing the next year.

He gained his School Certificate and University Entrance at the Cadet School, was posted as a Private soldier to the School of Infantry, achieving the rank of Cpl in quick order. He attended a very early post- war OCTU in 1955 and was posted back to the School of Infantry as a 2 Lt I/C Tactics Wing the next year.

I have chosen to cover Brian’s early years in some detail because it helps to explain the man that he was to become – driven, goal-orientated, self-reliant and self-centred. Impatient with the foolish and the fearful. A perfectionist. Detailed planning and deliberation was behind everything that he undertook. Everything was a battle to be won.

Brian’s commissioned career saw him serve as a Platoon Commander with 1NZ Regt in Taiping before returning to NZ as a Captain and Adjutant at WWCT in Wanganui. He was then variously at Tactical School, the Plans and Staff Duties Directorates at the General Staff, or abroad. He had topped his Staff College exams and was selected to attend the US Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth.

During this time he married and had two daughters who both grew up to become fine professional and family women. Sadly. Jan and he lost an infant son, who succumbed to SIDs, shortly before Brian’s return from Leavenworth.

He also achieved a remarkable Economics degree with honours from the University of London as a correspondence student. He spent several years out of the circuit as our ABCA Liaison Officer in Canberra and did not therefore return to operational soldiering until his appointment to command and trainV6 Company for service in Vietnam.

He also achieved a remarkable Economics degree with honours from the University of London as a correspondence student. He spent several years out of the circuit as our ABCA Liaison Officer in Canberra and did not therefore return to operational soldiering until his appointment to command and trainV6 Company for service in Vietnam.

Due to some mistimed recruiting, V6 soldiers in the main were to have less than six months training before their deployment. This required considerable innovation and the active support of a fine cadre of senior NCOs and WOs. Most of the Cpls had already been blooded in Vietnam and were to undergo their Section Commander training concurrently with the Riflemen’s Corps Training. Their temporary absence gave the Lance Corporals time in which to develop the skills so critical to the junior leadership role that he would demand of them in Vietnam. Brian abandoned the thoroughly over-worked Tekapo and Little Malaya training areas and opened up an entirely new area on the West Coast. There he rotated his sections and platoons through a rigorous bull-ring sequence to get them up to speed in a hurry. It worked. V6 was able to integrate seamlessly into their host ANZAC battalion and quickly demonstrated their mastery of small group manoeuvre in the jungle environment, usually operating in patrols of half section strength. After an operationally challenging several months, V6 Company was recovered in good order to Singapore in late 1971.

Brian was to return to the General Staff in NZ in mid 72 and in due course to take up the post of Commandant the Army Schools and later Commander of the Army Training Group Waiouru. Having enjoyed what amounted to an independent command with V6, and performing exceptionally well in that role, Brian found difficulty accepting the constraints that were then impacting on our rapidly downscaling little Army. He found funding and equipment restraints, that were continually being imposed on the conduct of training, irksome in the extreme. Many were the occasions when his capacity for planning exceeded his diplomacy.

I remember well an occasion when I, as GSO1 Ops Land Force HQ, was to accompany the then Commander to Waiouru to witness what he muttered what was to be Brian’s summary execution for his temerity in exposing some serious flaws in a plan that he was set upon. Fortunately, the weather closed in and the RNZAF Cessna pilot declined to proceed beyond the escarpment above Waiouru. So the axe did not fall that day. In fact, the axe never did fall. Brian simply lost faith.

His concept for a professional little Army that was capable of doing a real job was just not the way that those making the decisions apparently saw things. As he saw it, the Army was not getting leaner; it was just smaller. It was not pointier: it was becoming increasingly top-heavy. He despaired at the loss of purpose resulting from short-sighted political policy. And so, after nearly four decades of service, Brian sought early retirement.

His move into the civilian sector saw him take up an appointment as Registrar of Massey University. He continued in this role for several years until again, he was to find that his views were becoming increasingly at variance with those of the top brass. He was not able to reconcile the academic imperative of a University with the “bums-on-seats” approach that was to gain such damaging traction in the 90’s. And so, they parted company, leaving Brian free to lobby elsewhere.

By the mid 90’s the discontent among veterans of the war in Vietnam, at the way they had been neglected and abused by successive post-war administrations was becoming a cause celebre, even to hoi palloi. Capitalising on the initiative and tireless work of a number of others, whom I do not name for fear of omission, Brian became the figure head, mover and shaker and point of contact for “Parade ’98 – Vietnam Remembered”. This was a massive full-time undertaking which was to chart the course for all later Vietnam veteran initiatives to right the wrongs flowing from that unpopular deployment. With the exception of the RNZAF, folk at the very top of Defence HQ (and the Army General Staff especially), far from assisting in the project, actively obstructed it. No request for support was too small to refuse. No accommodation, catering, transport, flag bearers or, uniformed contingent was forthcoming. Indeed, 2/1 Battalion which had raised a contingent, was directed to stand down. The Generals even refused to wear uniform to the Governor General’s reception for the Australian Deputy Prime Minister who was to be the principle guest. This was a sad demonstration of just how wide was the gulf that had been opened between the incumbent high command and any sense of a duty of care for its old soldiers.

In stark contrast, the reception given by the citizens of Wellington, who clapped and cheered continuously as the veterans marched, stumbled and hobbled through the downtown streets, was overwhelming. Most veterans were brought to tears. The ceremony the following day, at which Jim Fisher gave a profoundly moving address, was equally emotional. The signal success of this event proved to be the catalyst for many improvements to veteran administration that were so long overdue. Parade ’98 was perhaps Brian’s most significant contribution to the profession of arms outside of his exemplary command of V6 Rifle Company Group.

In stark contrast, the reception given by the citizens of Wellington, who clapped and cheered continuously as the veterans marched, stumbled and hobbled through the downtown streets, was overwhelming. Most veterans were brought to tears. The ceremony the following day, at which Jim Fisher gave a profoundly moving address, was equally emotional. The signal success of this event proved to be the catalyst for many improvements to veteran administration that were so long overdue. Parade ’98 was perhaps Brian’s most significant contribution to the profession of arms outside of his exemplary command of V6 Rifle Company Group.

Somewhere within this tumultuous period, Brian married again. How his new wife, Catherine, was able to deal with his obsessive involvement in causes and politics, I do not know. That she did, is much to her credit.

If there was one issue that frustrated Brian to the last, it was the question of medalic recognition of the acts of valour by a number of his chaps in Vietnam. Until the day he died, he did not believe that an arbitrarily applied quota, administered by a foreign government, was an appropriate way to manage such recognition. In the end, he simply lacked the energy to carry the day and institutional ennui and a rapidly advancing malignancy prevailed.

Brian had a very fine mind. Conditioned no doubt by the experiences of his child hood, he absorbed an encyclopaedic knowledge of international and current affairs and military history. He was diligent and highly effective in the execution of his duties and fiercely loyal to those he lead and with whom he served. He was a real soldier, but too late (or perhaps too early) for the really big battles. Even so, he developed a formidable battlefield persona and revelled in any opportunity to exploit it.

Brian was above all an honourable man, and I am proud to be his brother. Norera, tena koutou, tena koutou, tena koutou katoa. Another fine exemplar from the barracks of the Regular Force Cadet School.

*Geoff places Brian into Williams Class although The Favoured Few has him as a member of Greville. His explanation: Brian could not enlist until his 16th birthday, he did not join Greville until 1 Jun 1951 (for which, due to the circumstances, the head shed made an exception). He graduated the following year with Williams, which was the class he identified with.

Thanks to Geoff Monks for this tribute to Brian and to Bob Davies for (small) pieces of added commentary.

Military Arts

British troops advance through the gas at the Battle of Loos, 1915

Dulce et Decorum est

by Wilfred Owen

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori

Wilfred Owen was a Great War poet. The poem Dulce et Decorum est is rated as one of the most famous of all war poems and probably the best-known of all of Wilfred Owen’s poems. It was written in response to jingoistic pro-war verses popular at the time. Owen wrote the poem in 1917 at Craig Lockhart hospital in Scotland, where he was being treated for what was then called shell shock. He was there at the same time as another war poet, Siegfried Sassoon. On release after his treatment Owen went back to the front. He was killed, age 25, in the first week of November 1918, the week before the Armistice was signed. (Photo – Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen.)

Wilfred Owen was a Great War poet. The poem Dulce et Decorum est is rated as one of the most famous of all war poems and probably the best-known of all of Wilfred Owen’s poems. It was written in response to jingoistic pro-war verses popular at the time. Owen wrote the poem in 1917 at Craig Lockhart hospital in Scotland, where he was being treated for what was then called shell shock. He was there at the same time as another war poet, Siegfried Sassoon. On release after his treatment Owen went back to the front. He was killed, age 25, in the first week of November 1918, the week before the Armistice was signed. (Photo – Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen.)

If poetry isn’t your thing, you might be interested in a series of novels written by Booker Prize-winning author, Pat Barker – Regeneration, The Eye in the Door , and The Ghost Road. They form the Regeneration trilogy and are based around Owen and Sassoon at Craig Lockhart, their treatment by a progressive psychiatrist, William Reeves, and the Great War fighting they were involved in. They are among the best books I have ever read.

If poetry isn’t your thing, you might be interested in a series of novels written by Booker Prize-winning author, Pat Barker – Regeneration, The Eye in the Door , and The Ghost Road. They form the Regeneration trilogy and are based around Owen and Sassoon at Craig Lockhart, their treatment by a progressive psychiatrist, William Reeves, and the Great War fighting they were involved in. They are among the best books I have ever read.

Just because of a certain event overseas:

The School provided Guards of Honour for two US Presidents. Who were they, when were they, and where were they?